Data Journalism

Deutsche Welle: “The Real Plan was half a copy of the German model”

Former president of the Central Bank of Brazil and one of the creators of the Real Plan, Gustavo Franco says that Brazil was inspired by Germany’s plan during the hyperinflation of the 1920s

First published in Deutsche Welle on 8/7/2019

Click to see the original article (in Portuguese) and the portuguese version

Seven years before joining the economic team that would formulate the Real Plan and put an end to uncontrolled price rises in Brazil, Gustavo Franco looked into the causes and effects of German hyperinflation. More precisely, the period from the 1920s, during the Weimar Republic, to the recovery after the Second World War. When he defended his doctoral thesis at Harvard, little did he know that this experience would equip him years later to identify similarities and differences in Brazilian inflation.

In the month in which the real celebrates 25 years in circulation, the former president of the Central Bank of Brazil (1996-1998) and one of the mentors of the Brazilian currency, said in an interview with DW Brazil that, in fact, the Brazilian plan is a copy of the German model “in half”.

Take a look below

- Germany’s experience inspired the creation of the Real Plan in Brazil

- DW Brazil: You are one of the scholars of the effects of the German hyperinflation of the 1920s. What are the differences and similarities with what happened in the 1980s and 1990s?

- The experience is really very similar to the Real Unit of Value (URV). How did it inspire the Brazilian case?

- Twenty-five years on from the start of the Real Plan and in the midst of a degree of monetary stability, does it still make sense to worry about inflation?

- At an event held this year in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, you said that agendas discussed at the time of the Real Plan still haven’t changed 25 years later. What are those agendas?

- Brazil now has low inflation and a Selic rate that is also at one of its lowest levels. These combined conditions should be favorable for an economy on the rise. Why is Brazil slipping back into growth?

- One of the criticisms leveled at Minister Paulo Guedes is that he places too much trust only in the pension reform and fails to act on other strategies for restoring employment and attracting investors. What would you do differently?

- From 1994 to 2019, the real has accumulated inflation of 508%. Much higher than that of the dollar in the period, but still lower than that recorded in the first half of 1994 alone. Was this result to be expected or is it cause for concern?

- You once said that in 1998 we reached an American level of inflation…

- Read also:

In Germany in the 1920s, an experiment was tried with two currencies simultaneously: the Reichsmark, which devalued due to high inflation, and the Rentenmark, which remained stable. The population adopted the more stable currency on a daily basis, which allowed the country to control inflation.

Germany’s experience inspired the creation of the Real Plan in Brazil

This experience inspired the creation in Brazil of the Real Value Unit (URV), which was in force from March to July 1994, while the cruzeiro real (CR$) also existed. However, only the latter was used for payments, and the URV was stamped on products as a reference to the “real price”. The URV was pegged to the dollar and was therefore stable, while the CR$ changed daily due to inflation. With the real (R$) coming into force in July 1994, the URV and the CR$ were extinguished.

“In Brazil, hyperinflation didn’t leave a trauma like it did in Germany, where the consequences of inflation go far beyond the direct economic effects.” Gustavo Franco, economist

In this interview, the economist also talks about the risks of inflation returning and what he thinks of the current government’s economic policy. He says that priority agendas that were discussed by the Real Plan team have still not been implemented, one of them being the pension reform. For him, President Jair Bolsonaro still needs to establish his pro-market economic policy.

DW Brazil: You are one of the scholars of the effects of the German hyperinflation of the 1920s. What are the differences and similarities with what happened in the 1980s and 1990s?

Gustavo Franco: It has many interesting parallels. And the solution in our case is a variation on the German Rentenmark, implemented in the summer of 1923. You could say that the starting point is similar, because inflation was in the range of 40% to 50% per month, that’s the situation in Germany at the end of the winter and beginning of 1923, and that’s the situation when the real was made.

In both cases, a kind of second currency was introduced. But in Germany it was a much more disorganized and much richer experience, which was the introduction of the so-called Notgeld, which are emergency currencies with a stable value, indexed, which were issued by private agents, factories, churches, town halls. These things began to proliferate and with great acceptance. And this was similar, in the Brazilian case, to the spread of contracts with indexation throughout the economy.

In Brazil, there wasn’t so much private issuance of currency, but there was a widespread practice of indexation. Then comes Rentenmark, the German state decides to create a second Central Bank, which will issue a second currency, however, built with the same logic of an indexed currency, with a stable value. And what happened to Germany from the moment the experiment began is that we have two currencies: the Reichsmark, which is a common, bad currency, and the Rentenmark, which is another national currency, good, just as good as the foreign currency.

What happened was that the coexistence of the two payment currencies caused an explosion in the prices of the old currency, because nobody wanted to accept the old currency anymore, and they wanted to get rid of the old currency they had and just get Rentenmark, the good one. German inflation, which had been running at 50% a month, reached 30,000% a month at its peak in November 1923.

The experience is really very similar to the Real Unit of Value (URV). How did it inspire the Brazilian case?

Gustavo Franco: Here we saw something very brilliant in the Rentenmark, which served to end German inflation, but with the problem of inflation exploding, because there were two payment currencies. So what we did in Brazil was a Rentenmark in half. It was a Rentenmark that was only a currency of account, not a currency of payment. People couldn’t refuse the cruzeiro real to accept the URV, because the URV wasn’t enough to pay.

It was the same mechanism as Rentenmark, and it was extremely useful for coordinating expectations, contracts, prices, wages and everything else. But it didn’t cause inflation to explode. The Rentenmark lasted a few months in Germany. The URV lasted a few months and when it became a currency, it changed its name to the real, and the cruzeiro real ceased to exist. So we never had both currencies circulating simultaneously. Our inspiration came from Germany.

Twenty-five years on from the start of the Real Plan and in the midst of a degree of monetary stability, does it still make sense to worry about inflation?

Gustavo Franco: Yes, there’s always the risk of it coming back and there’s an ongoing discussion in the country about memory. And a very common complaint is that in Brazil hyperinflation didn’t leave a trauma like it did in Germany. In Germany, the consequences of inflation go far beyond the direct economic effects, it’s a controversial point in historiography.

Here in Brazil, one of the mechanisms to reduce interest in taking more drastic adjustment measures to solve our problems was a certain denial: “Brazil is not experiencing hyperinflation.” It was a common thing not to use such an ugly word, “because it only happened in those very extreme cases in Europe” [they said]. And there was a reference to Germany, as if Germany hadn’t had inflation very similar to Brazil’s, except in recent months.

In Brazil, it was as if it “wasn’t that serious”, “it’s not that serious, so it doesn’t need so many reforms, so many precautions”. But indeed it was. But fortunately, even if the political perception is a little complacent, in the Real Plan, the institutions were very much protected from the vices that would bring inflation back. So it’s very difficult to produce the same phenomenon again today.

At an event held this year in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, you said that agendas discussed at the time of the Real Plan still haven’t changed 25 years later. What are those agendas?

Gustavo Franco: One of them is the pension reform, which has been tried several times and has passed in bits and pieces. There are others in the fiscal sphere: privatizations that didn’t happen, stopped halfway through. This is the case with the energy sector. I think we managed to complete some things, but not others. There’s still a lot to privatize, the state is still too big. More specifically, things relating to the Fiscal Responsibility Law, we should have made more progress, and we failed.

One symptom of the failure was the fiscal performance of the states, which is very poor. In some large states it’s as bad as it was 20 years ago. This is regrettable. In other words, we would have had to advance in caution and institutions linked to the budget to make it more realistic, more defended from political pressures.

Brazil now has low inflation and a Selic rate that is also at one of its lowest levels. These combined conditions should be favorable for an economy on the rise. Why is Brazil slipping back into growth?

Gustavo Franco: I think there are several reasons. There was an extremely strong cyclical recession, and recessions like this are sticky, as they say in English, the recovery is more painful and takes longer than when they are normal recessions. This one was very violent. There are some tensions in the economy on the supply side that are not trivial. One of them is the fiscal crisis itself, but there is an important by-product of this, which was a collapse in the oil and gas and heavy construction sectors, as a result of Operation Car Wash. Some of the main players in infrastructure are companies that are in financial stress, some of them in judicial reorganization.

There’s no doubt that there was a certain amount of stress on the banking system and it cast a cloud over the credit landscape, a factor that slowed down the recovery. Confidence needs to be restored, and we had an extremely atypical election in Brazil, the impeachment of President Dilma [Rousseff], we had a year of quiet and then came a political crisis around President Michel Temer, and a very difficult and paralyzing election, with the business world frightened by the possible return of the PT (Workers Party).

It became a question of whether Brazil would go the way of Venezuela or Argentina. This paralyzed private investment. And then Jair Bolsonaro is president, and he still needs to establish his pro-market economic policy. That’s how the economy minister [Paulo Guedes] is seen. But there are still doubts as to whether this president will be able to implement this program, the main item of which is the pension reform, which is very difficult.

The recovery is taking place, but very slowly. It lost a bit of momentum in the last quarter. I suppose that with the passage of the Social Security amendment, the recovery will accelerate a little more.

One of the criticisms leveled at Minister Paulo Guedes is that he places too much trust only in the pension reform and fails to act on other strategies for restoring employment and attracting investors. What would you do differently?

Gustavo Franco: It’s a difficult process to control, because it depends a lot on the political dynamic with Parliament. And the pension reform, because of the postponements over the years, ended up becoming a huge thing. And it’s very difficult for any parliament to deal with a seven-page constitutional text on a very complex matter.

In other countries, the Constitution is very simple, smaller, more principled. Not in our case. So when you have to change something like that, it’s a giant headache, because each piece of the law, of the constitutional text, affects a specific social group and makes it very easy to organize small veto coalitions.

So this kind of reform is very difficult. So it was strategically chosen to go first, because all the others are much easier, and that’s when the government is strongest and most organized. It could be stronger and more organized, but that’s what we have [laughs]. And it’s moving.

From 1994 to 2019, the real has accumulated inflation of 508%. Much higher than that of the dollar in the period, but still lower than that recorded in the first half of 1994 alone. Was this result to be expected or is it cause for concern?

Gustavo Franco: It’s just that the first 12 months of the real have made a big difference. In the first 12 months, IPCA inflation was 33%. Over all these 25 years, average annual inflation has probably been 7%. However, the first year spoils the average a little. We only had double-digit inflation after that in 2003, because of the currency devaluation in the transition to the Lula government. And it was further ahead in 2011 and 2012, with Dilma, reaching 10%. That’s a spectacular performance for us, considering we’re a former hard drug addict [laughs].

Small episodes back to old vices. It’s not exactly like the dollar, but it’s the closest we could have come in our entire history. Perhaps the best 25 years in terms of inflation the country has had since the 19th century. Yes, it’s something to be proud of. I don’t think we’ll ever have 33% a year again, as we did between July 1994 and July 1995.

And look, we’re heading towards an inflation target of 3.5%. We’ve already had 1.5%, it was in 1998, in fact my last year as president of the Central Bank, it’s the record: 1.6% in the IPCA, which was important to detoxify the organism.

You once said that in 1998 we reached an American level of inflation…

Gustavo Franco: At that moment there was a structural break. The most difficult thing in economics is when you manage to change people’s behavior, to structurally change the way they view inflation. In 1997 and 1998, we achieved this by keeping inflation below 5% a year for those two years, which was an experience that no living Brazilian had ever had. You’ll only find Brazilian inflation below 5% a year before the First World War, before 1914.

That was a dazzling experience for those people and for all of us, and it created popular support for stability, which I think was hopeful at first. But the whole product had to be delivered. If it had stopped in the middle, everyone would have been happy in 1996, but inflation was still running at 20% a year. You can’t stop there, you were still intoxicated.

We had to go up to the American level. You know, when you go to the spa you have to get to the right weight, there’s no point in just getting close, otherwise you’ll put the weight back on [laughs]. So we got to the right level, which was important for detoxifying the body.

Read also:

- Deutsche Welle: “Plano Real foi uma cópia do modelo alemão pela metade”

- Deutsche Welle: Brasiliens neuer Präsident Lula da Silva: Totgeglaubte leben länger

- Deutsche Welle: Tem parente alemão? Saiba se você tem direito à cidadania

- Deutsche Welle: Cresce número de brasileiros com cidadania alemã

- Deutsche Welle: Em 15 anos, 170 mil brasileiros obtiveram cidadania europeia

- Deutsche Welle: Como se tornar um turista sustentável

- Deutsche Welle: “Bolsonaro ignora o meio ambiente e o que a ciência diz”, afirma Thomas Lovejoy

- Deutsche Welle: O potencial turístico de unidades de conservação no Brasil

- Deutsche Welle: Discordâncias entre Brasil e Alemanha podem afetar comércio?

Back to Home | Back to Portfolio | Back to Latest

-

Articles2 years ago

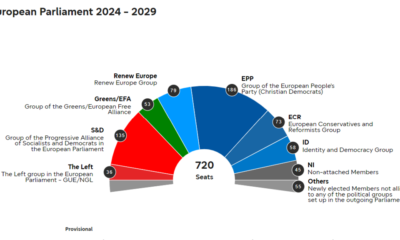

Articles2 years ago2024 European Elections: Check the results by country in charts and maps

-

Articles2 years ago

Articles2 years ago6 Valuable Tips for Building a Successful Journalist’s Portfolio

-

Data Journalism2 years ago

Data Journalism2 years agoDeutsche Welle: Could disagreements between Brazil and Germany affect trade?

-

Academia1 year ago

Using topic modeling to analyze freedom of information law requests